MUSINGS

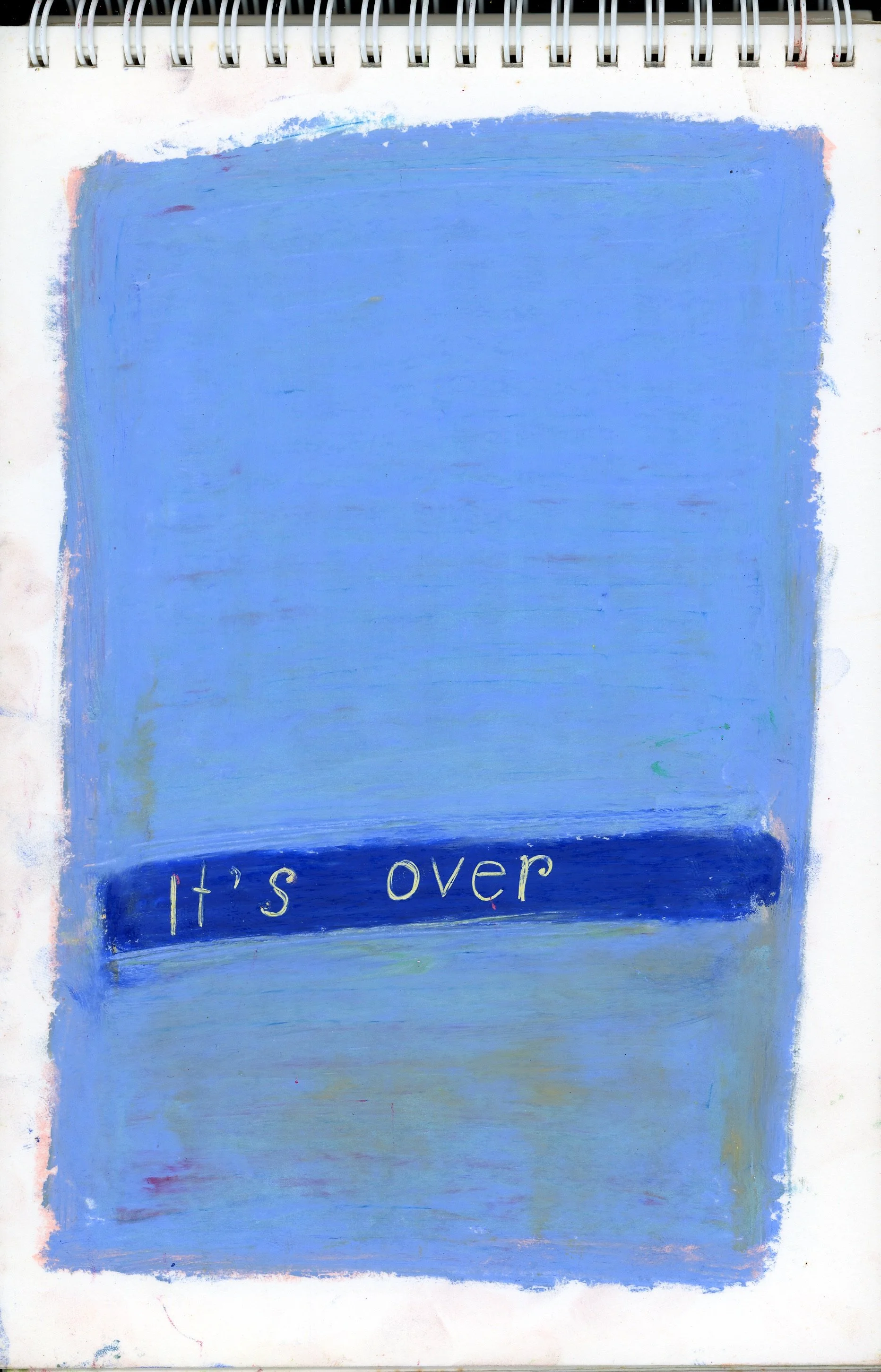

It’s Over - The End of a Death Sentence & Depression

This month I am sharing the stories behind the drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE which is available in USA, Europe, UK and for pre-order in Australia.

This is one of my favourite drawings, because of its simplicity and the sense of liberation I felt when I placed the light blue all over the page.

Thanks for reading I am Alive! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

After cancer treatment, the protocol at the Institut Marie Curie was to have 6 monthly check ups for the first two years. And then annual check ups for years, 3,4 and 5, in case of any recurrence. With each check up looming, I would be engulfed with the capacious fear of, “Has the cancer come back?”.

The difficulties of the first three years of checkups were compounded with having to deal with PTSD, depression and the hormonal nightmare of surgically induced menopause. At the time, I would half joke that if I had a gun, I would shoot myself out of my misery. As each year went on, the symptoms reduced but ask anyone who knew me at the time: I was angry for having to go through such fatigue and pain. I was finally dealing with the pandora’s box of emotions, which I had suppressed for years…

What I did not know at the time is that trauma awakens trauma which has been suppressed. My experience of radiation awakened earlier traumas I had not dealt with. This came out as rage within me. It kept rising and rising. Rage and sadness. I bought a punching bag and gloves which I hung in my room, to help move the rage out of my body. My nervous system was so deregulated that the smallest hiccup in daily life could set me off into a mess of low-coping response and tears.

I was living in rural South India in the temple of my spiritual teacher. I knew it was the right place to heal but I was in grief of having had to give up ‘my life’ in Paris… and my work as a photographer/ film maker. I yearned for for all I had lost: my vitality, my health, my joy, my strength, my courage, my ease of navigating life, my sexual being, my sense of humour... I was worn out. Everything. Absolutely everything felt hard. Each day was a struggle. And I didn’t know if I was ever going to get better.

Why was Paris so important to me? My mother left the family in Australia and returned to France when I was 13 years old. It was a devastating experience and I visited her every Christmas vacation. In 1991, at the age of 22, I had studied 2 years in Japan and completed my Masters in Japanese at Sydney University. I had been so focused on proving to myself (to prove to others) that I could do this. I then spent the following year teaching Japanese and with my friend Maria, co-translated the book that became, Tao Shiatsu. We signed off the book in Japan and with the money from the translation, I moved to Paris. I was tired of all the study I had done. I wanted something totally different. I had so wanted to live in Paris, because I yearned to live in the same country as my mother. There was a desire to catch up on the years I had missed with her as a teenager.

I worked as a tour guide for Japanese and taught English and Japanese. I fell in love with Géraud who lived in Montmartre. The work was a means to an end so that I could stay in Paris. I rented a studio in rue Simon Dereure on the top of the hill of Montmartre. It overlooked a park and if you leaned out to the left, there was a stunning view of the Sacred Coeur. I loved Paris but I longed for my creative soul to be expressed… but had no idea how to make the leap. Then 18 months later, I met James who shook my soul (not in a kind way). He was my catalyst and probed me, asking what was I doing with my life? I didn’t know. I was unhappy with my relationship. I felt lost. I had left my job and was freelancing and was just making ends meet. I needed to get out of this survival mode. I found a job setting up a french company office in Sydney… this would be a place to work out my next step.

In Sydney, I worked really hard. I was a creative being in the corporate world. I felt like my wings had been clipped. I could not open the windows on the 18th floor of the building. I prayed a lot during that year for guidance and direction for my next step in life. At night, I would dream of the cobblestones of Montmartre. They were calling me back, “Reviens, Reviens…”. I would wake up in the morning, with such yearning to return to Paris.

I had a list of potential creative things I could do in Paris which would better suit my soul. This list included exhibition design, shiatsu healer, documentary film maker, but I didn’t have a plan. I kept praying and meditating on this list, how could I be creative AND earn a living so that I could stay in Paris? Then after eight months in the corporate world, at daybreak, I was woken by this very loud voice, in my left ear, “Documentary film!”. There was my answer.

I had saved up my money and a few months later, I returned to the cobblestones of montmartre. I greeted them every day with joy. I moved back in to my old studio at rue Simon Dereure, and started knocking on doors asking documentary film producers for work. I ended up working on the first BBC/ ARTE coproduction as a production assistant on a film on Albert Camus. This was the beginning of my learning.

Paris was very generous with me. At the same time of working in documentary film, I developed my documentary photography and the creative being I had been yearning to become, flourished. I always had enough. I appreciated the anonymity of Paris. I fell in love with the city and the life it offered me.

The dread of stepping into that building of so much suffering.

But when I got radiated at the Institut Marie Curie, the love affair with the city ended abruptly. It now represented a place of torture. And I wanted nothing to do with any memory of my torture.

Each visit back to Paris, back to the Institut Marie Curie would have me spiralling. I hated it all. I hated the hospital, as I was aware of how much suffering was in the building. I would feel such dread and fear but always be charming with the staff. It was a cover. I could not separate the experience of the past from the present.

Then by year four, I had learnt to regulate my nervous system, and with this, came more ease of activities in life. I would still crash regularly but my bandwidth could deal with more. I still hated going through the process of returning to Paris, to the hospital but I could see that I could cope a little better.

At the five-year check up, if the results were “clear of cancer”, I would no longer be in the danger zone of the cancer returning, I would not have to return for any more check ups. This was a huge milestone.

The results? I was clear.

What happened next? I was taken completely by surprise. The feeling of a low, heavy ceiling lifted from above me. The sensation was so palpable. I could breathe differently. At that very moment, I understood that, for the previous five years, I had had this invisible death sentence looming above my head. And now, it had gone. I felt my depression lift, my body relax. I was receiving permission to move forward in life. The worst of it is over.

It’s over.

LOVE POEM TO RADIATION (the love poem that took 15 years to write)

Drawing 1 of LOVE POEM to RADIATION 2025

Last December of 2024, as I was writing the introduction to my book of drawings, I AM ALIVE - Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma through Art, I found that I finally had enough distance to revisit the experience that had been my worst nightmare: 8 days and nights of brachytherapy radiation. The radiation had devastated me, but it had also saved my life.

I wanted to reflect on this complex relationship to the treatment. The machine had simultaneously hurt me but also cured me by completing burning out the deadly tumour that was in my cervix. I wanted to imagine a return back to the night before treatment, to that moment where I found myself alone, in my room with the radiation machine. But this time, it would be different. I would bring with it, the wisdom I had accumulated in my own healing and the experience of my own recovery. The most important aspect of this exercise, is that, this time, I was going to feel safe.

In 2009, the evening before I commenced radiation, I was filled with horror. I did not know how to contain the experience of knowing that I was going to be burnt alive, around the clock. To help me process this fear, I began a monologue with my soul, wanting to see the entire experience as that of oneness. I wanted to see the radiation machine, the radiation, my tumor, the window, the tree outside my window, every nurse or doctor who came into my room as one. All was interconnected. All was one. This was my way of coping.

As I burned in radiation, the experience was extremely painful and my body felt trapped. I maintained the interconnected experience through constant prayer but I also felt rage as the machine burned me each hour.

Here is the love poem. I imagine writing it as I sit next to the radiation machine, the night before treatment in my little room of the Institut Marie Curie in Paris which had one small window overlooking a tree… while holding the insight, the experience of healing that I hold within me after, 15 years of healing and life.

Drawing 2 of LOVE POEM TO RADIATION 2025

To my persecutor, the silent unwelcome guest, the radiation machine.

You are my greatest terror and nightmare.

Yet I have no choice but to befriend you as your radiation burning will heal me.

For the duration of the treatment, I will take you on as a spiritual being. I will see you as Divine.

It will feel like you are torturing me, every hour, 24 hours a day.

I shall not sleep.

I shall not eat.

You will burn me alive.

I will feel the insides of my body cook.

My mother will tell my brother that when she visits me, my room smells of burnt flesh.

Then when the week is over, your radiation/burning will devastate me completely.

I will lose my mind, my peace, my vitality and my joy.

It will take me years to recover.

However, ultimately, you will save my life.

You will burn away this deadly tumor.

And you will also burn my entire pelvis area and the organs within.

It is because of you that I will have an extension of this life.

For a year after your radiation, I will not be able to fall asleep peacefully.

In the dark of the night, my body will feel that you are there, beside me.

My body will wait for that dreaded « click».

The click that begins the internal burning.

It will take five years for the sense of a looming death sentence over me, to lift.

Seven years later, I will see a drawing of Sita sitting on a pyre, being burnt alive and I will confidently say that I know that very experience.

For the next 14 years, every time I return to Paris, (a city I once so loved ) will be in dread and fear because the city will be the reminder of my place of torture with you.

Yet in this room, the night before radiation begins. It is ever so quiet. Just you and I. A vigil for us both, before the reckoning.

I will need to see you as the Divine, I will need to see this all playing out as the Divine otherwise I simply won’t get through this.

I will want to run

I will be pinned down

There will be no escape

This is it.

You will be my torturer, my grace, my saviour.

We will be one. We are Divine.

I will come out of this alive.

This is my process of surrender

Final drawing of LOVE POEM TO RADIATION 2025

Devastation and how I Learnt to Feel more Connected to Humanity

Breathe in the fear

The experience of devastation is not only related to having a life threatening illness. Devastation can happen in any form and every one of us, one day, will (very likely) be hit by it. When that blow came for me, my world stopped. I remember how rapidly, my question of, How could this be happening to me?, slid, lightspeed into, Oh ###k, this is happening to me.

The floor disappearing beneath me.

The sensation of free-falling without the parachute. (I am scared of heights)

This is happening to me.

I journeyed through the myriad of doctor appointments and choices, and shared waiting rooms with other people with similar life threatening illnesses. Then, I began treatment. The waiting rooms of the Institut Marie Curie in Paris were filled with the most unsuspecting people. The chic elderly woman in a silk hermes scarf who held tightly to her leather clutch while sitting with her helper, the African woman in her 50s with her colourful cobalt blue headwrap, the man in his well fitted suit and yellow tie, probably in his 40s. The young mother wearing a wool cap to hide her lost hair accompanied by her exhausted husband. The manual labourer with his rough hands and thick fingers. The middle aged women, tightly groomed, possibly an executive from the corporate world. Nobody, I realised was spared. As my hospital visits continued, I shifted from my own self pity into being fascinated to know that this is not only my suffering. This is happening to thousands of people around the world at this very moment.

I spent hours in the waiting rooms of Institut Marie Curie in the 5th arrondissement of Paris. Sometimes I would find myself, breathing in the fear of my own experience and breathing in the fear of every person in the waiting room with me. Breathing it all in. Connecting to a part of humanity’s suffering. And then, I would breathe out love, sending love to myself and those with me in the waiting room, to those in the hospital floors above me and those around the world.

It sounds counter intuitive to want to do this. I often wished to be “rid” of pain, of the difficult experience of treatment. I wanted ease and comfort. However when I was in the thick of the fear, the suffering - there was no ease nor comfort. I wanted it to end but before that happened, I needed to go through it. And, I discovered, it is better to go through something with others than alone.

The surprising thing is that the sense of inter-connectedness from this experience, meant that I felt a lot less lonely in my own suffering (which felt insurmountable at times) and felt a profound connection with humanity and our commonality of suffering. This sense of connection gave me courage to keep going.

Drawing as a Vital Act

When I was putting the book together a friend asked me, “Why did you draw so much?” as she saw piles of over 100 Sennelier drawing pads stacked one on top of eachother in my studio in South India.

The thing is, that I never planned to draw. I was a photographer before this all happened and I had an affinity with the medium of photography. The camera was an extension of myself and I had this connection with people that was extremely natural, and you could see this in each portrait I took.

Photography requires movement. I knew that from a bed, the possibilities of photographing were going to be very limited and as a part of my treatment I was going to be stuck in bed, isolated in a radiation room, undergoing treatment for 20 minutes every hour/ 24 hours a day / 7 days, I knew I needed an alternative to channel my creativity.

Part of my preparation for radiation treatment at Institut Marie Curie in Paris was a visit to an art store where I bought white Italian clay, acrylic paints, pencils, drawing pads, fimo and sennelier oil pastels. I packed these into my bag for my 7 day hospital stay. I also added a small camera, some movies, 2 books, crochet hooks and wool and my notebook.

The night before I was in the radiation room alone waiting for my 5am wake up call to take me into surgery to insert the radiation rod inside me. Terror rose. I picked up the oil pastels for the first time and drew the sensations of terror inside my body directly onto the page.

When radiation began, it felt like bullets shooting up my vagina. I began to burn internally. The experience was horrific and I knew I could not move because that would move the radiation rod which was inserted in me. Nothing could console me. No book, no movie, the written word, crocheting… nothing. I was alone with the radiation machine.

I reached out for the oil pastels and began to place colour on the page, and just as I had done the previous night, tuned in directly to each emotion I was experiencing. And then I would get another colour, and tune in again. And this way, I kept laying colours on top of eachother, kept feeling into each emotion. And then I started to scratch on the layers and other colours appeared. Each drawing was my lifeline. A vital act. Each drawing was also an anchor for me to remain connected to myself and to not lose my mind.

Printing I AM ALIVE

I thought it was going to be an easy enough process. I was wrong.

The last few months putting the book together had been grueling. In retrospect, I should have got on a plane and finished the book with the designer and publisher in person. There is such value in working face to face. Another mistake learnt.

On May 5, earlier this year, I arrived in Stuttgart, Germany to print my latest book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma through Art.

I had attended the printing of my catalogue, Love it and Leave it - Australia’s Creative Diaspora. We had printed in Singapore. It was black and white and a very smooth process. My imagination never went to the space that it could be a vastly different experience/

So what was the difference between the prints?

Very simply: the personal…

Love it and Leave was about other people’s stories.

I am Alive is my story.

Every drawing in the book has an aspect of my soul imprinted into it. There are the drawings from when I am being burnt alive. The drawing from when I am fighting for my life. The drawing from when I want it all to end. The drawing of not coping. There are drawings of trauma, depression, grief in all their colours. I lived them. Each of them is a part of me.

To see these images each with a fragment of my soul be spat out of the printing press at such a high speed was dizzying and overwhelming. The emotions of this triggered the sensations of going through cancer treatment again… How could I explain this to anyone around me? I couldn’t find the vocabulary. And printing this book was a professional setting: I needed to stay cool and centred. The machines were dedicated to bringing my book into reality that day. Tomorrow was reserved for another book. This was not the day to fall apart. All I wanted to do was hide and cry. At one part of the day I found myself in the toilet, gathering my sense of being. I wished so deeply that I was not going through this alone. I knew I really needed someone by my side… but how could I have known I was going to be triggered like this? I thought I was over the trauma of my treatment. That was 16 years ago… How could I be reacting this much? I reminded myself of how much I had worked to recover.

Breathe deeply. Come back to my body.

I got through the day and went to the main station to get a train to Frankfurt. I was early and sat on the platform. My head in my hands. I was enraged with how the day had gone. I should have been more careful, I should have foreseen to accompany me today, someone to help me through this. I was done. I called a friend, “I never ever want to see that book again. I want it all to be thrown away. This was not worth it. **** it.”

A month later, when the first book arrived, I felt no joy. I was still overcome by the experience that had happened in Stuttgart. This is a sign for that things are not OK and that I still need to pay attention to what is going on.

Time plays such an important part of healing. Time and focused attention on the issue - which is what I did. I took care of the parts of me that hadn’t felt safe, that were overwhelmed by time in the printing, that confused the printing with me being in radiation. Separated. Brought back together. Whole.

And now, two months later, I have come to befriend the book. I am ready to share it with others and let it reveal its journey to me.

Printing of I AM ALIVE in Stuttgart, Germany

Offset printing - I was being shown how each colour is measured.

I AM ALIVE : Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma through Art

My new book, I AM ALIVE - Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma through Art is coming out this Autumn and I want to share behind the scenes of making the book (which took a whopping 16 years)… yes, you read correctly 16 years.

The book was described as, “An unflinching and luminous account of illness, faith, resilience, and the transformative role of art in finding one’s way back to life.”

The story begins in 2009. This is the first chapter to give you an idea of how the story kicks off:

—————————————————

The doctor clicks her pen, looks down at the worn carpet where her feet

follow the swivel of the chair. She doesn’t look me in the eye. “You have

Stage 3 cervical cancer.”

Then she tells me in a matter-of-fact manner, “We do not know yet if the

cancer has spread to your lymph nodes. If it has, the survival rate is low.”

I can no longer feel the chair beneath me.

What else is she saying?

A roaring silence fills me.

I am free-falling through the sky. No parachute. Nothing to hold onto.

Is this it? I am 39 years old.

—————————————————

The book is primarily drawings that I began in hospital, the night before brachytherapy (radiation for cervical cancer) and I continued to draw over the following 7 years as I navigated through the depths of depression, physical healing from very intensive radiation and the tricky pathways or recovering from PTSD. Until I slowly, every so slowly returned to life. Drawing was an urgent lifeline, my witness that I still existed in this world.

By the time I had forged my way through the seven year journey of returning to life, my drawings had changed profoundly. Drawing became an opportunity to spend quiet time with myself (which I really appreciated). These times gave me access to listen to what my soul wanted to draw, to express.

The reader essentially gets to see this arc of 14 years of drawings within 184 pages, along with a text that gives context to the drawings.

Below, is the book cover which is a self portrait of me during brachytherapy radiation. It may look like a very simple drawing. However, the experience of radiation was so traumatising that it took me 3.5 years before I could draw this image of my experience.

So now is the time to share this work… so I will be posting more! Stay tuned!

How did I start drawing?

It’s a question I’m often asked, and the answer takes me back to a time before my treatment for Stage 3 cervical cancer...

It’s a question I’m often asked, and the answer takes me back to a time before my treatment for Stage 3 cervical cancer. I was a photographer and filmmaker—drawing had never been part of my creative process, aside from the occasional doodle in a notebook. But everything shifted when I was preparing for a seven-day brachytherapy radiation treatment at Institut Marie Curie in Paris. I knew I would be confined to a bed for continuous radiation, and I needed more than just physical items to bring with me—I needed tools that would help me mentally navigate the ordeal.

The idea of being "pinned down" felt suffocating, but I wanted to turn it into an opportunity for expression. I carefully curated a list of items that would keep me occupied and help me process the experience through creativity. Drawing, as it turned out, was one of the first things I thought of.

Here’s what I packed:

Books

Ink for drawing

Sennelier oil pastels

Notebook for writing

DVDs (comedies)

FIMO (colorful plasticine)

Crocheting supplies

Camera

Blog to update daily

Paint and canvas

White Italian clay (small batches)

Sticky tape, glue, scissors

Sound therapy machine

My bag for the hospital was also filled with a folder of all the cards and messages loved ones had sent me, as well as all the items mentioned above. These creative materials became more than just items—they were lifelines. Each of them, in their own way, helped me reclaim some control over my body and mind, and drawing, in particular, became a way for me to transform my inner world into something tangible.

The act of creating during that time, no matter how small or imperfect, became an essential part of my healing. And in that hospital bed, I began to draw for the first time. It wasn’t just about surviving the treatment—it was about finding a way to express the complexities of my experience. Drawing gave me a voice when words failed. It allowed me to connect with a part of myself I hadn’t known before—a part that still needed to be seen, even in the midst of pain and uncertainty.

Radiation Begins

There was a strange dance that unfolded over the next seven days—a rhythm dictated by the relentless pulse of the radiation machine. Every hour, without fail, the machine would roar to life, delivering its charge 24 hours a day...

There was a strange dance that unfolded over the next seven days—a rhythm dictated by the relentless pulse of the radiation machine. Every hour, without fail, the machine would roar to life, delivering its charge 24 hours a day. I lay there, pinned down, as the machine worked tirelessly to destroy the cancerous cells within me. Yet, while parts of me were being "cooked" and destroyed, I felt a connection to something deeper. I clung to the mantras I silently chanted, feeling the universal life-force flow through me. It was as though, in the midst of cellular destruction, I was simultaneously being held by a force larger than myself, keeping me grounded, keeping me alive, even as parts of me died.

This contradiction—of life and death intertwined—was disorienting. The physical reality was undeniable: my body was breaking down, and my cells attacked hour by hour, minute by minute. I felt trapped, imprisoned in a position that I couldn’t escape. The radiation schedule was brutal—25 minutes of radiation, followed by the desperate attempt to catch fleeting moments of sleep before the machine would start again. My back ached constantly from being unable to move, and the desire to simply stand and stretch became an obsession. The inability to act on this need only deepened the sense of captivity. I was pinned down, both literally and metaphorically.

Words, at that moment, were useless. How could they capture the violence of what was happening to me? The pain, the intensity, the inescapable sensation of being torn apart from the inside—it was beyond articulation. The tools I had brought to pass the time—books, clay, crocheting—became meaningless in the face of this all-consuming experience. The thought of using them felt absurd, irrelevant. But the oil pastels… they were different.

The oil pastels allowed me to access something beyond words. There, in that sterile, confined space, their vivid colors became my lifeline. Drawing wasn’t just a distraction; it was survival. I could take those pastels and scratch at the paper, releasing through lines and color the unspeakable terror I was enduring. The act of drawing was raw, almost primal. It wasn’t about creating something beautiful; it was about expressing the inexpressible, making visible the emotions that words could never convey.

Every stroke of pastel across the paper felt like a release. Each line, each curve, mirrored the internal chaos, the pain, the fear, the strange dance between destruction and life. The colors—bold and aggressive—became a reflection of what was happening inside me. I didn’t have to explain or rationalize; I simply let the pastels do the talking. This act of creation, of making something tangible out of my suffering, became a way to cope with the violence I was experiencing. In the midst of radiation, in the moments where I could not move, drawing allowed me to escape in a way nothing else could.

In those seven days, I discovered a new language—one born from necessity, from the depths of my struggle. The colors of the oil pastels helped me access the unspeakable, transforming the horror of radiation into something I could see, something I could control, even if just for a moment. It was not about art or beauty. It was about survival.

Staying Sane

During radiation, I needed to stay sane. I knew that the relentless grind of treatment could push me over the edge, could make me lose my grip on reality if I didn’t find a way to ground myself...

During radiation, I needed to stay sane. I knew that the relentless grind of treatment could push me over the edge, could make me lose my grip on reality if I didn’t find a way to ground myself. I focused on chanting mantras internally, drawing on that connection to a life-force beyond my physical experience, but it wasn’t enough. I needed to express myself, to give voice to the chaos inside. In these moments, I would reach for my drawing pad.

Pinned down on my back, unable to move freely, it was important that the pad was small enough to hold with my left hand while I drew with my right. My movements were restricted, but even within those limitations, I could still create. I tuned in to what I was feeling in each moment, letting the raw intensity of my emotions guide me. Deep green, grey, sky blue, red—each color had a meaning, each hue a reflection of something simmering inside.

I’d begin with the first layer: a thick, opaque surface of oil pastel that mirrored the emotion demanding to be felt. I pressed the color into the page, letting it take shape, building a layer of that particular feeling until something shifted within me. The change happened once the emotion had been heard, acknowledged. These feelings, however intense, didn’t just want to be experienced—they wanted to be expressed.

Once that layer was complete, I’d pause, listen again. What emotion was next? Which feeling wanted to make itself known? I’d reach for another color, layering it over the first, sometimes completely covering the original color, sometimes letting them coexist. Each stroke of pastel carried a weight, a message, a release. I listened, responded, and let the emotions dictate what color came next, which direction to take. The process was deeply meditative, each step a dialogue between me and the experience unfolding within me.

As I drew, tiny balls of oil pastel gathered on the page, little round bits of wax that collected on the white hospital sheets beneath me. They smeared and smudged, staining the sterile environment with color and life. In that space, amidst the medical machinery and the cold, clinical surroundings, I found warmth in those smears of color.

Then came the scratching. I’d take a bamboo pencil and carve into the layers, etching the unspoken words that needed to be released:

Help.

This feels too hard.

Only 103 hours left of radiation.

Each time I scratched away at the colors, my emotions carved into the page, my mind found a place to travel—a place where I could escape the relentlessness of radiation. The simple act of drawing gave me access to life, to the deepest part of my internal being. Radiation felt like an attack, like my body was being burnt alive from the inside, but drawing was my way of fighting back. It allowed me to reclaim a sense of control, to create in the midst of destruction.

The art I created wasn’t meant to be seen by anyone else. It wasn’t about beauty or aesthetics—it was about survival. Each stroke, each layer, was a lifeline. The act of creating in that moment felt vital, as though it was the only thing keeping me tethered to myself.