MUSINGS

REHAB FOR THE SOUL

Images from I AM ALIVE: When Grief Becomes Song, and Song Becomes Medicine

How grief began to lift during a New Orleans workshop, sparked by a haunting blues voice and nurtured by creative friends: trauma recovery, healing through music, and how the body remembers to live again.

Text: Let it rain. Let it pour love. Shine. Sunbeam. Rehab for the Soul. Pull the ropes baby. Shake it. Bake it. Dance. Zebra Love. Fish Jive. Goat Dance. New Orleans 2013.

I visited New Orleans with a friend to attend a workshop with Hillary & Bradford Keeney

.What a joyful discovery of the life force this was! I describe the experience in chapter 19::

Chapter 19 from I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma through Art.

Images from I AM ALIVE: Since my Diagnosis

Text: Since my diagnosis, I was in the constant motion of loss. Everything that I thought I was or I thought belonged to me, was a part of me, I had to lose or give up or let go until I was on my knees. I was no more. Then I became everything. I have all I need. I am so grateful I lost the debris.

Today is the first day of the second part of my book, I AM ALIVE. These are images from the time of about 4 years post treatment, onwards.

The outlook of these drawings is definitely more uplifting, the trauma is not far away… yet I start knowing how to regulate my nervous system. My body has settled in to itself after the instant menopause. There is a sense of acceptance and at times, liberation. In this part of the story, I am discovering who I truly am. There are moments when I still slip into deep sadness and overwhelm but life feels a lot more manageable.

In sharing these images, I really hope that others whom have gone through a huge crisis will gain strength or courage from this story. When we are brought to our knees, it is possible to stand up again and return to life. It takes time, a huge amount of self compassion and patience. And it can happen.

And for care takers, I know the book sheds light of the internal process of the person going through a crisis (health or otherwise) or deep difficulty.

Keep shining the light.

I AM ALIVE launched in NYC!

It was a truly heart felt night and to be surrounded by so many people I love and have known over the decades was a gift.

I AM ALIVE in conversation with Sonya Bekkerman with Beneville Studio

Above is the link to video of the conversation Sonya Bekkerman led at Beneville Studio earlier this month.

It was important for me to have Sonya lead the talk as this book carries so much weight, trauma, sadness, acceptance and joy.

Sonya was one of the first people I shared my drawings with on her first visit to India in 2012. She was navigating a completely different world to mine: I was in my 3rd year of recovery from cancer, planting trees, praying, wearing sarees and living at the guest house of Sri Narayani Peedam in South India while Sonya was running the Russian department in Sotherby’s in NYC. Sonya belonged to the world I knew before I was diagnosed but by 2012, but that world felt so far away from me as I struggled with depression and PTSD. I immediately enjoyed her company: she was visiting India with her sculptor uncle, who was larger than life. Big heart. Huge embrace to life. Sonya was intellectually sharp, deep in her observations and very funny. They both made me laugh a lot. When she looked at my drawings for the first time, she wept. I was moved that she was so emotional in seeing the drawings. She understood.

Sonya has quite the talent of creating a narrative. She linked up my earlier photography work (Russia, China, Australian creatives living around the world) as my era of travel and looking out into the the world.

I was searching to understand what it meant to be a human being.

Next, she swerved into the next chapter of my life: DIAGNOSIS & CRISIS where my next series is of me photographing myself in waiting rooms, in between scans, blood tests and doctor visits at Institut Marie Curie in Paris as I traversed the diagnosis of stage 3 cervical cancer. These images, she noted were of me turning my camera on myself for the first time. Until the talk, I hadn’t even noticed this shift. It was a natural response for me to keep photographing my world. And then the photography stopped: I was stuck in bed in radiation for 7 days and 7 nights, pinned down. And this is where the drawing began.

Now looking back at the talk, the narrative seems so obvious… however, I just couldn’t see it until that night. I had felt that my life as a photographer, as an artist had stopped with the diagnosis. But now I see is that I was doing was responding to my circumstance. The spirit of the artist had never left me.

I am so grateful for how Sonya navigated the talk with such attention and wisdom. It was an emotional talk to give and I wasn’t expecting to start choking up when I read out, Love Poem to Life. I heard myself apologising for my tears, “I am sorry.” Then I quickly corrected myself, “I am not sorry.” Then I explained how I never ever imagined to be able to return to life the way I had, for which I am extremely grateful. The grief is always there tucked away, appearing unexpectedly to remind me that this is a process to honour. And the joy is there to be shared and experienced.

Thing weren’t really as I thought they were…

Learning that things were not really as I thought they were.

Day 17 of 21 days sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma with Art published by Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam.

Text: Learning that things were not really as I thought they were.

When I drew this image, I had completed treatment a month earlier and was struggling with a very weakened body, PTSD, surgically induced menopause. It was at this time that I could not remember the names of friends: this showed me how overwhelmed my brain was. I found it difficult to fall asleep at night. I did not feel safe within my body.

As I went deeper into therapy, I discovered that I had told myself quite a different story to how things really were growing up. This time was an opportunity to turn up for myself in the most authentic way. I was so depleted that I could no longer be what others wanted me to be. I was over with people-pleasing. I began to be live my own truth. This was extremely challenging yet liberating at the same time.

Meditation: What is my truth?

Somatic Experiencing

Day 16 of 21 days sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma with Art published by Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam.

Text: Charred on top: no life

Underneath: burnt, raw, pulsating, alive

In the depths of my suffering at the time, returning to life was something I never had imagined could be possible.

This image was drawn after sessions of somatic experiencing (see Peter Levine’s Waking the Tiger).

I had been disassociated from my body for over a year, and part of the process of somatic experiencing therapy was to ever so gently, with tiny steps (so as to not overwhelm) enter into the sensations of my body which had been intensely radiated.

This is what I discovered: underneath the skin felt burnt, raw yet pulsating and alive. The top of my skin felt charred like a forest fire.

Although there was a sense of pulsating life in the body, my mind was in such a state of shell shock, that I did not really believe or know that I would get better. In retrospect, I find it fascinating that when I found the safe space to sit in curiosity about how my body felt, I associated my body to the forest fires I knew from my childhood in Australia: what looked like charred devastation always had a life force underneath… life would return in time. The innate wisdom of my body knew that it would return to life.

It was extraordinary to experience first hand, how this human body did return to life. It took years, and lots of attention, therapy, love, meditation, prayer, connecting with nature… but it did happen.

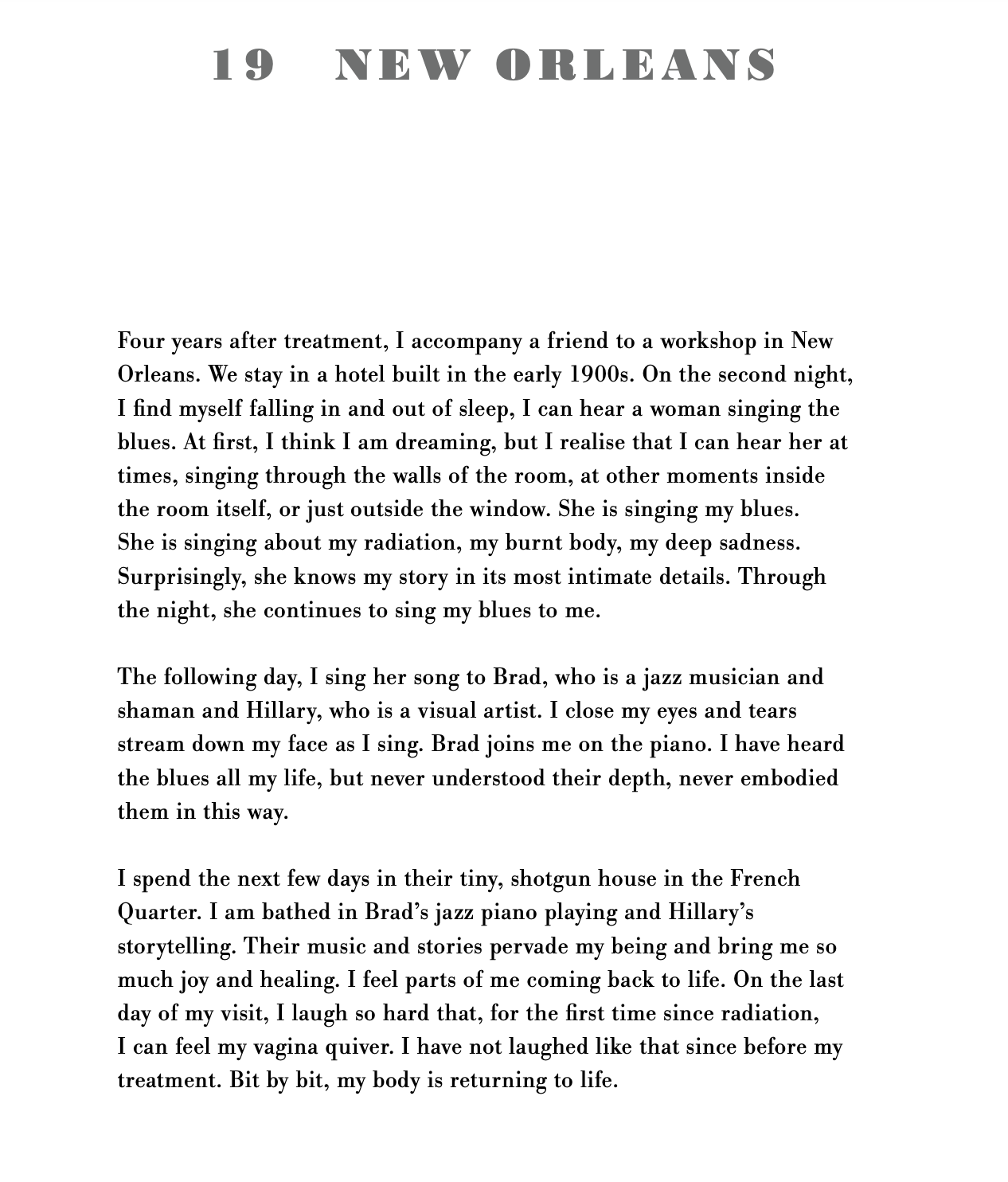

Suspended in Time

Day 15 of 21 days sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma with Art published by Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam.

Text: suspended. No idea where all this is going to take me.

I had been through treatment. I was cured of cancer but was not healed from the experience of treatment. My body was worn out and in shell shock. I was too weak to return to my old life/ my job… I had entered the game of waiting. This was far from comfortable as a process, particularly for someone like me who had been so dynamic in life and had the ability to create and make things happen.

This was my experience of completely surrendering myself to the process of healing and life.

The Deep Song of Rage

Day 13 of 21 days sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma with Art published by Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam.

During radiation treatment and the surgeries, I was in high vigilance, survival mode.

What I was not expecting was the anger and rage that arose after the intensive medical procedures. I could no longer recognise who I had become. It took years of therapy, writing, drawing, tears, frustration, meditation, prayer, planting trees and letting go… to untangle and dissolve the intense feelings around the experience, as well as any anger I had suppressed earlier in my life. I had to befriend it all.

I ended up buying a punching bag and gloves and hung them in my room. It was really helpful to punch the bag until I was exhausted (and as I was already depleted… this activity rarely lasted for longer than a minute).

I made it through. Nothing to prove to anyone.

Day 12 of 21 days sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma with Art published by Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam.

I made it through. That part is over. I can feel it in my body. I will never be the same and although the scars are there - life feels so much light and richer. Nothing to prove to anyone.

Breathe

Breathe

Day 11 of 21 days sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma with Art published by Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam.

Sometimes this is all we need. To focus on the breath. Come back to the breath. Ultimately, this breath of the Life Force is all we have.

During my recovery process I created many drawings around the act of the breathing/ the breath.

They say I am cured - why do I feel so unsafe?

They say I am cured. Why do I feel so unsafe?

Day 10 of 21 days sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma with Art published by Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam.

This was a strange place to be in. When I created this drawing, I had been given the “all clear” from the medical world. I was cancer free. And when my loved ones, friends and family heard this, everyone gave a huge sigh of relief and got on with their lives. Nathalie is no longer in danger.

It is true, I was no longer in danger but I was far from healed. Being cured and healed are two vastly different worlds.

I still struggled with everything and most of all, I did not feel safe within my body. At night I could not fall asleep because I was fearful that the radiation machine was going to click on (I could not separate the past experience of not feeling safe to my present day where I actually was safe). I also wondered, how long was I going to be “clear” for? Was the cancer going to return next year? The experience felt heavy and very lonely. It was really hard to talk to anyone about this. One friend who had been through cancer, understood. My therapist listened too and week by week, focused on bringing me back to my body through somatic experiencing. I prayed every day. I cried every day. Being alive felt overwhelming.

I am not alone: understanding trauma for the first time

The skin feels numb. The surface between the world and my inner broiling cannot express anything.

Day 9 or 21 - sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma.

I remember sitting in a taxi in traffic. As I looked through the window, and saw people walking on the footpath, I was so aware that there was a world out there that I was not able to be a part of. My emotions were boiling inside. My skin felt numb. I could not express myself. My body was stuck in very unfamiliar territory.

To feel completely separate from the world is not an unusual experience but since I was a child, one thing I did feel pretty consistently was the oneness with my world. But that was no longer the case.

In the following days after this moment in the taxi, a friend suggested I read Peter Levine’s Waking the Tiger. This is where I began to learn about the process of trauma. The words I read, spoke to me. This is the first time that I understoo

d the radiation is a traumatic event and I am still stuck (frozen) in that energy.

Here is the drawing after I have read the first few pages of WAKING THE TIGER:

Text from above image:

In trauma, the mind becomes profoundly altered.

For example in a car crash, a person is protected initially from emotional reaction and even from a clear memory or sense that it really happened.

THIS speaks to ME.

These remarkable mechanisms allow us to navigate through those critical periods hopefully waiting for a safe time and place for these ALTERED states TO “WEAR OFF”

YES YES

The altered state was my experience of radiation

I feel I am beginning to understand the trauma inside of me. I am not alone in the experience.

All I need is a cooked meal and my feet massaged

People keep asking me is there anything I need or want? All I need is a cooked meal and my feet massaged.

Day 8 of 21 days: sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma.

This drawing is from 2009 when I had completed treatment, was cured of cancer and was extremely weak, depressed and in shock.

I spent the day lying on my sofa resting, drawing, praying or watching movies.

Loved ones around me were at a loss. At this stage, there really wasn’t much anyone could do for me. I know this happens for many people recovering from a huge medical intervention or accident where the body needs rest. My answer needed to be a very practical one and both answers were acts of nurturing: a cooked meal and my feet massaged (to help me get back into my body).

Let me be

Let me be

Day 7 of 21 days sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma with Art published by Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam.

When I drew during the first seven years of recovering from radiation, it was to prove to me that I was alive. Each drawing was a witness that I was still in the land of the living. I never imagined that I would make a book, but over the years, seeing the amount of drawings I had made, it seemed obvious to a handful of friends that there was something there to share.

The obstacle in creating a book was that, for over a decade I could not look at most of the drawings. There was too much pain in them. I would feel overwhelmed. Many drawings of the book hold a very strong energy of a particular (very difficult) moment or emotion lived. So, the sketch pads were placed in boxes, the boxes were piled upon eachother, until I had enough distance to return back to those moments lived within my body.

There are a handful of drawings from the first 7 years, where I can feel an inner sigh of relief and this is one of them. There is no residue of trauma here.

In the process of recovery from intensive radiation treatment/ surgically induced menopause, depression, PTSD… there were many people who had the best of intentions: how I should be… what I should be… had I tried x, y z? These best-of-intentions felt overwhelming and that something was wrong with me. Why, after years, was I still unwell, still struggling with everything when I had been cured of cancer within the first months of my diagnosis?

It is a curious place to be. But how could anyone understand how brutal the treatment had been and how I had been stripped away of everything that made me, me? Stripped away of my vital force, my desire to live, my inner strength, my joy, my sexual being... My body had been internally burnt around the clock for 7 days and nights and it was taking time to recover.

What I longed for was space to just be.

The message of this drawing, Let me be reminds me, there is nothing to do, no one to be. It appears as a message to myself that it is OK to relax and just be me. I am enough.

Looking back at the time, I thought I had been stripped away of desire for life. However, I see in this drawing that I did have a desire: for those around me to let me be.

It took time, however, I did heal. I did return to life and I became whole again.

Meditation: How does it feel to sit and simply be, you? No expectation of any result. Simply be… you.

Reminder to Self : it takes time to heal

It’s been knocked out of me: my courage, the fearlessness, the joy, that strength I have so depended on.

Day 6 of 21 days of sharing images from my book I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma through Art.

When the experience of radiation treatment and multiple surgeries brought me to my knees, I could no longer recognise myself: the courage, the fearlessness, the joy, the strength I had so depended on to carry me in life, had simply been knocked out of my being. It took years for me to return to myself. In retrospect, I did have courage as I did stay with life (I did not throw myself under a bus which I had considered an option). And interestingly, at a time I felt far away from life, in this image, I drew the shape of the egg

The act of drawing as my witness: I am Alive

Text: The act of drawing, of creating is my witness to knowing I AM ALIVE. I am here. I exist. I did not die. I am here. I am here. Je suis là.

Day 4 of 21 Days sharing my drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma Through Art, published by Schilt Publishing.

A drawing of rejoice. I can still feel the sweetness of being in touch with the life force when I drew this.

Being brought to my knees

Now I know how it feels for a person to give up.

DAY 5 of 21 DAYS sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma through Art.

Until the experience of radiation treatment, I had a huge desire to life and a surprising capacity to manifest my goals in the material world. I would have a vision of something I wanted to achieve and would work relentlessly until it came into being.

I am Alive is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This was also my way of survival: I had trained myself to ignore my own needs since I was a child. As a result, I had no idea how to give myself space to listen to my own needs: I filled up my life with action. This was also how I was able to quieten the chaos within my own being and keep the residue of trauma silenced.

Treatment brought me to my knees, I could no longer recognise myself: I had lost my desire for life. I lost the strength in my body. I had finally understood what it felt like to want to give up. I had to learn what it meant to take care of my own needs. This felt like a foreign language. And it took me years to retrieve all the internal pieces and become whole again.

Meditation: What makes you feel whole?

Emotional healing is slow and more complex than physical healing

The emotional healing slow and more complex than physical healing

DAY 3 of 21 days of sharing images from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma through Art

Art accompanied me through radiation, depression, PTSD, surgically induced menopause and the long road back to myself.

If you’ve ever wondered how creativity can be medicine for the soul, this book is for you.

The Importance of NOW

I can only think of NOW

Day 2 of 21 days sharing an image a day from my book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma through Art, published by Schilt in Amsterdam.

As I recovered from intensive radiation treatment, multiple surgeries and surgically induced menopause, when everything felt so overwhelming, I would come back to the essence. These were 2 things: the NOW moment and my breath. To focus my mind completely on the NOW, brought me relief that I so needed.

Meditation: How present can you be right now?

Asking Nature to Heal Me

Tonight I asked for the support of every leaf, ever tree, every blade of grass, every insect.

Over the next month, I am sharing drawings from my book, I AM ALIVE - Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma Through Art. This drawing was a plea to Mother Nature to support me in my healing.

Today is day 1 of 21 days.

As a child, I remember the awe I would feel when I observed the natural world reflected within a dew drop on a leaf. This was a profound experience of interconnectedness, an understanding I had always felt intuitively, growing up. When I was with Nature, I felt the presence of the Divine in everything.

As a teenager, when I learnt that the Australian Aboriginal culture saw the earth as Mother, it completely resonated with me. Then, when I went to do my post grad studies in Kyoto, Japan I would often skip classes and cycle to the temples where a particular festival was taking place. Here, I saw the exquisite worship of Nature through Shinto and Zen Buddhist ritual. My intuitive experience of Nature as sacred was reflected in these rituals. Although culturally, it was a very foreign land, my soul understood deeply. Although it looked nothing like home, my soul felt at home in a land which worshipped nature.

In 2005, I found another “home” in South India, a place where Narayani, Mother Nature is worshipped. From the rooftop of the guest house, I could also see the Kailash Giri Hills, a sacred mountain range where sages (also known as Siddhars) have meditated and prayed for centuries. I would gaze at the Kailash Giri Hills and I knew I had arrived to my spiritual home.

Fast forward 5 years, I was in the process of my recovery of radiation treatment, surgically induced menopause, depression and PTSD. I was now living in the very same guest house and had installed a hammock on its rooftop where I could see the sacred Kailash Giri hills.

One afternoon, I was feeling particularly down and I prayed to Narayani / Mother Nature, asking for support. I was very specific in my request as I wanted support from every aspect of Nature around me: I asked every leaf, every tree, every blade of grass to support my recovery. I soaked up the sensation of Narayani / Mother Nature holding me and bringing life to this body that was feeling so heavy and stuck in trauma and depression. Later that night, I got out my pastels and created the above drawing.

Facing my Fear & How I Learned to Ask for Support.

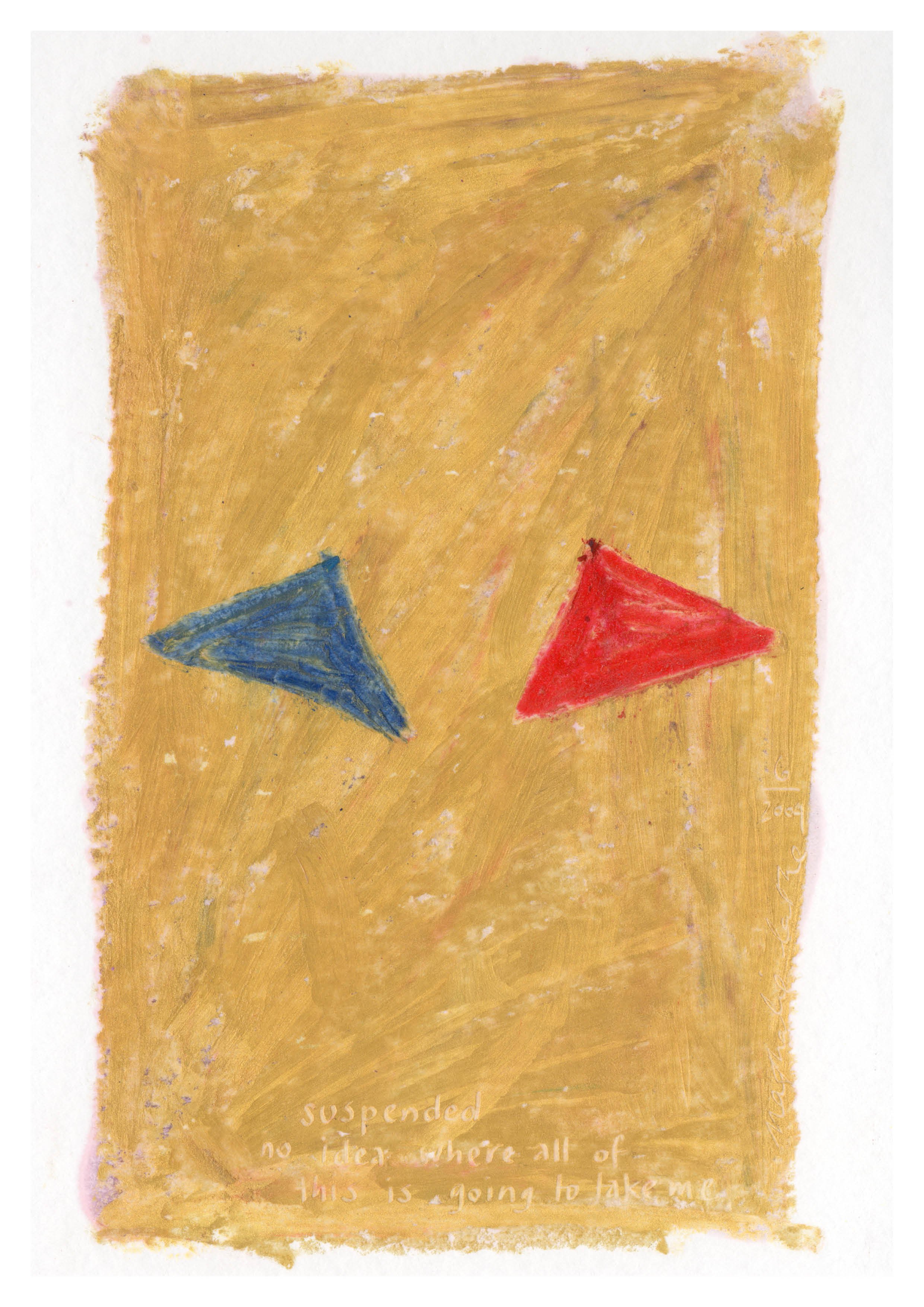

It’s All Going. Orange = Surgery

This month, I am offering readers the stories behind some of the drawings from my recently published book, I AM ALIVE: Creating Resilience and Healing Trauma through Art.

As my tumour had reduced I was exempt from six months of chemo (talk about a miracle… that story is for another day). The final part of my treatment included a radical hysterectomy. The surgery took place a month after I had completed brachytherapy radiation (being radiated internally, every hour for 24 hours a day over 7 days).

I had been completely knocked down by the radiation. I could no longer recognise myself. I had been a spiritual warrior of Oneness for the seven days and nights of radiation. It had been a profound spiritual experience. But after radiation, I had to return back to my body: a body where the entire pelvic area had burnt internally. A body that was devastated. A mind that had shut down from the pressure of the experience.

Radiation had drained me of my life force. I had never, ever felt this weak. My brain had slowed down completely: I could barely string thoughts together. I could remember faces but could no longer connect the names to the face of my friends. Getting to the toilet was a momentous effort: then I would have to wait for the pee to pass, it felt like pissing razorblades each time. What has happened to me?

The night before (surgery and drawing my fear)

I visited the gynecologist to prepare for the hysterectomy. She asked if I had saved my eggs? I had not. Why?

“Your entire reproductive system was destroyed during radiation.”

What??? This hadn’t been explained to me.

“You have gone through surgically induced menopause”

What???

I had been so struck by so much already, it was too much to process any more information. It had never occurred to me that I could lose my eggs during this process.

I had already had three surgeries in the last month on top of the radiation. That was it. I did not want any more interventions. A friend knew of my fear of general aneasthetics, of being cut open and stitched back, so he recommended a book Prepare for surgery : Heal Faster by Peggy Huddleston. I followed its recommendations religiously.

Hysterectomy 4 May - drawing the fear of going through surgery

I was already constantly chanting Om Namo Narayani, my mantra to Mother Nature in my mind. It was my internal anchor that connected me to Mother Earth. Peggy Huddleston’s book encouraged me to meditate, to prepare my subconscious to feel safe and feel supported, so, I spoke to my surgeon - to understand that I was truly in good hands. I messaged my friends who were spiritually connected and asked them to pray for me during the lead up to the surgery. I also gave them the time I was to go into surgery, so they would be mindful to be with me during it and coming out of it. The night before surgery, friends came over and we did a small fire ritual, called a puja (which I had learnt in India) to feel the support of my community and the universe.

It was definitely not protocol in France as surgeons have a very scientific way of looking at the world, but I asked my surgeon to do something he had never done before. I said to him, “When I go under anesthetic, please tell me you are going to take good care of me. And when you have finished the operation, please tell me that it has gone OK and that I will heal fast.” By this time, my surgeon was used to me asking weird and unusual questions, so he kindly agreed.

The moments before I went under, I remembered all those who were thinking of me, praying for me. I was supported.

After the hysterectomy, I woke up with a bloated belly which had been stapled back together. I had been cut across the lower part of my stomach from one pelvic bone to the other. The pain was excruciating. I had a morphine drip which I could administer and I maxed out my dose on the first day. I shared a room with a woman who had received a mastectomy. We looked into each other’s eyes. We didn’t need to say a thing. We both knew that we had traveled to deep and painful places.

When my surgeon came to see me for the post surgery visit, he told me that he had spoken to me before and after the surgery. I was amazed that he had done this and remembered to tell me. I felt like a pioneer within the french medical system by creating a more meaningful connection between the the doctor and the patient.